Affiliation:

1Gastroenterology A, Ospedale Borgo Trento-Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata di Verona, 37126 Verona, Italy

Email: v.mirante@libero.it

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2924-4717

Affiliation:

2Department of Internal Medicine, Ospedale Civile di Baggiovara, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Modena, 41126 Modena, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9886-0698

Affiliation:

3Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, 42123 Reggio Emilia, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8770-7329

Affiliation:

4Clinical Trials Center, Infrastruttura Ricerca e Statistica, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, 42123 Reggio Emilia, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6833-6318

Affiliation:

3Gastroenterology and Digestive Endoscopy, Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, 42123 Reggio Emilia, Italy

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2077-2609

Explor Med. 2024;5:656–673 DOl: https://doi.org/10.37349/emed.2024.00247

Received: January 29, 2024 Accepted: August 02, 2024 Published: October 21, 2024

Academic Editor: Lindsay A. Farrer, Boston University School of Medicine, USA

Background: Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography acute pancreatitis (PEP) is the most common complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Studies have shown that periprocedural administration of lactated Ringer’s (LR) solution may prevent PEP by multiple mechanisms. To assess the evidence for periprocedural aggressive hydration with LR alone or in combination with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as a preventive measure for post-ERCP pancreatitis, an updated systematic review was conducted.

Methods: Thirteen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were selected, including eight trials (a total of 2,095 patients) evaluating aggressive hydration with LR alone and five RCTs (a total of 1,550 patients) evaluating LR in combination with NSAIDs. A critical analysis of the data was conducted.

Results: RCTs evaluating the use of LR as monoprophylaxis showed that patients in the LR arm had a significantly reduced likelihood of developing PEP compared with standard hydration or placebo, and no lower likelihood than with indomethacin. RCTs investigating combined prophylaxis initially showed increased efficacy compared with single prophylactic strategies, but this superiority was no longer confirmed in more recently published trials involving larger numbers of patients.

Discussion: Aggressive hydration with LR is an effective alternative prophylactic strategy to NSAIDs for PEP. Further studies are needed to ascertain whether prophylaxis with a combination of aggressive hydration with LR and NSAIDs is more effective than prophylaxis with NSAIDs alone.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), introduced in the 1970s, is a widely used procedure for the diagnosis and especially the treatment of both benign and malignant biliary and pancreatic diseases [1]. Acute pancreatitis is one of the most serious complications of ERCP. According to Cotton’s criteria, post-ERCP acute pancreatitis (PEP) can be diagnosed based on the presence of at least two of the following criteria: new-onset or increased upper abdominal pain; increase in pancreatic amylase or lipase to three times the upper limit of normal 24 hours after endoscopic examination; subsequent hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization for two or more nights [2]. According to these criteria, the severity of PEP depends on the days of hospitalization and the development of pancreatic necrosis or fluid collections. Considering the large number of ERCPs performed, the economic impact of PEP is significant. With an incidence of 5%, approximately 35,000 cases of PEP occur annually in the USA, with an estimated cost of $199,500,000 [3, 4].

Over the last few years, many technical or medical interventions have been evaluated to reduce the incidence and severity of PEP. For example, prophylactic pancreatic stent placement (PSP) reduces the risk of PEP by approximately 60–70% [5–7]. However, the proven benefits of PSP must be weighed against the potential harms of this technique [8–10].

Globally, more than 35 drugs have been evaluated for PEP prophylaxis. Of these, only non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), particularly endorectal indomethacin, have been shown to be effective in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses [11, 12]. Therefore, this approach is currently recommended by several guidelines worldwide [13–16]. However, the use of NSAIDs in the prevention of PEP is still not universally adopted in clinical practice [17–20].

Peri-procedural hydration with lactated Ringer’s (LR) solution is a more recent and promising prophylactic strategy for PEP. The rationale for using LR solution in the prophylaxis of PEP is based on published evidence of improved outcomes in patients with severe acute pancreatitis treated aggressively with early administration of LR solution [21]. The mechanism of action of this strategy would be mediated by the maintenance of pancreatic perfusion [22–24] and the attenuation of local and systemic acidosis [25–28], which promote pancreatic enzyme activation. In addition, LR has also been associated with a reduction in inflammation when used for resuscitation in patients with acute pancreatitis. In fact, in an open-label study [27] and a triple-blind RCT [29] of patients with acute pancreatitis, LR solution reduced systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and blood levels of C-reactive protein compared to normal saline. It is, therefore, possible that LR also exerts anti-inflammatory activity in the prevention of acute post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Given the existing controversies on drug prophylaxis, an updated systematic review of available studies was conducted to assess the impact of aggressive LR hydration on PEP prophylaxis.

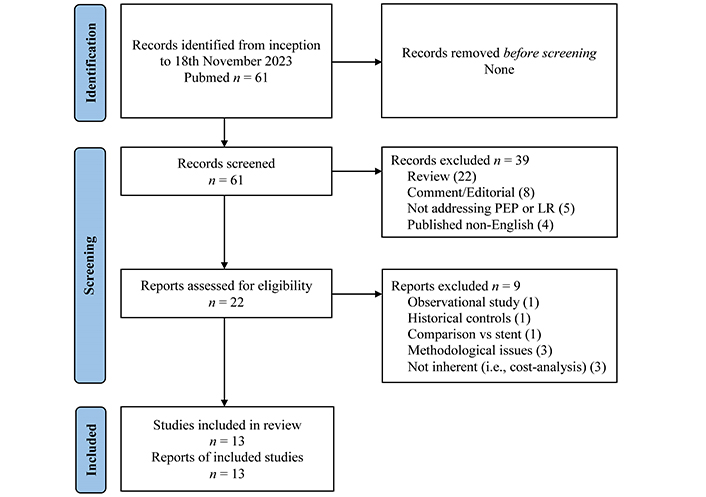

A comprehensive search of the PubMed database was performed, searching for trials from inception to 18 November 2023. Keywords used included a combination of ‘lactated ringer’, ‘aggressive hydration’, ‘NSAIDs’, ‘indomethacin’, and ‘acute post-ERCP pancreatitis’. The search was limited to studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals. In addition, the bibliographies of the retrieved articles were manually searched for cross-references. Only full papers were included. Our study conforms to the PRISMA 2020 checklist (Supplementary Table S1). The review was not registered (Figure 1).

PRISMA flow-diagram. PEP: post-ERCP acute pancreatitis; LR: lactated Ringer’s

Note. Adapted from “The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews” by Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. BMJ. 2021;372:n71 (https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71). CC BY.

The literature search using the methods described above identified 8 trials with LR alone and 5 trials with LR plus indomethacin in combination. The trials with LR alone and with LR plus indomethacin are reported separately (Tables 1–6). The strategy of bibliographic research and flow-chat of included and excluded trials are shown in Figure 1. The identified trials showed no ambiguity requiring an assumption of unclear information.

Tables 1, 2, and 3 summarize the main details of the trials discussed below.

Studies comparing aggressive hydration with lactate Ringer: study protocol design

| Author (country, year) [ref] | Study design | Infusion protocol | Comparison | Number pts | Female gender (%) | Mean age (yrs ± SD) | Patient related PEP risk | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buxbaum et al. (USA, 2014) [30] | RCT (2:1), multicentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg immediately after the procedure | Standard hydration [LR 1.5 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, without bolus] | 39 aggressive hydration23 standard hydration | 56.5 vs. 48.7 | 45 ± 17 vs. 43 ± 14 | Low and average risk | Previous sphincterotomyActive pancreatitisCholangitisChronic pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Electrolyte alterationsPregnancyAge > 70 yrs |

| Shaygan-Nejad et al. (Iran, 2015) [32] | RCT (1:1), monocentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg immediately after the procedure | Standard hydration [LR 1.5 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, without bolus] | 75 aggressive hydration75 standard hydration | 64 vs. 68 | 50.8 ± 13.5 overall | Low and average risk | Previous sphincterotomyActive pancreatitisCholangitisChronic pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Electrolyte alterationsPregnancyAge > 70 yrs |

| Choi et al. (Korea, 2017) [31] | RCT (1:1), multicentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 10 mL/kg before and immediately after the procedure | Standard hydration [LR 1.5 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, without bolus] | 255 aggressive hydration255 standard hydration | 45.5 vs. 45.1 | 57.0 ± 11.9 vs. 58.2 ± 12.4 | Average and high risk | Previous sphincterotomyActive pancreatitisChronic pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Electrolyte alterationsAge < 18 and > 75 yrsPost-surgical anatomy |

| Park et al. (Korea, 2018) [34] | RCT (1:1:1), multicentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg immediately after the procedure | a. Aggressive hydration NSSb. Standard hydration LR | 132 aggressive LR134 aggressive NSS129 standard LR | 53 vs. 56 vs. 55 | 59.0 ± 15.1 vs. 58.1 ± 15.5 vs. 58.9 ± 15.1 | Average and high risk | Previous sphincterotomySepsisActive pancreatitisChronic pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Electrolyte alterationsAge < 20 and > 80 yrs |

| Masjedizadeh et al. (Iran, 2017) [36] | RCT (1:1:1), monocentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg immediately after the procedure | a. Indomethacin 50 mg before and 50 mg after ERCPb. Nothing | 62 aggressive LR62 indomethacin62 nothing | 48.4 vs. 61.3 vs. 54.8 | 59.0 ± 15.1 vs. 58.1 ± 15.5 vs. 58.9 ± 15.1 | Low and average risk | Previous sphincterotomyActive pancreatitisCholangitisSepsisChronic pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*PregnancyBalloon dilation of papillaPancreatic stent |

| Ghaderi et al. (Iran, 2019) [33] | RCT (1:1), monocentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg after the procedure | Standard hydration [LR 1.5 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, without bolus] | 120 aggressive hydration120 standard hydration | 51.6 vs. 52.5 | 51.57 ± 13.5 overall | Low and average risk | Previous sphincterotomyActive pancreatitisCholangitisSepsisChronic pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Electrolyte alterationsPregnancyAge > 70 yrs |

| Guha et al. (India, 2023) [37] | RCT (1:1), monocentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg after the procedure | Indomethacin 100 mg endorectal | 178 aggressive hydration174 indomethacin | 69.9 vs. 71.3 | 44.0 ± 14.5 overall | Low and average risk | Active pancreatitisChronic pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Electrolyte alterationsPregnancyBreastfeedingAge > 70 yrsNSAIDs therapy in prior 7 days |

| Chang et al. (Thailand, 2022) [35] | RCT (1:1), monocentre | 3,600 mL LR in 24 h starting 2 h before ERCP | Standard hydration | 100 aggressive hydration100 control group | 47 vs. 49 | 50.9 ± 10.6 vs. 50.4 ± 12.6 | Low and average risk | Active pancreatitisChronic pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Electrolyte alterationsPregnancyAge > 65 yrsPost-surgical anatomy |

*: Cardiac, hepatic, respiratory, or renal insufficiency/severe disease; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; LR: lactated Ringer’s; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; NSS: normal saline solution; PEP: post-ERCP acute pancreatitis; pts: patients; RCTs: randomized controlled trials; yrs: years

Studies comparing aggressive hydration with lactate Ringer: results

| Author (country, year) [ref] | PEP (%) (experimental vs. control arm) | Severe PEP (%) | Hyperamylasemia (%) | Isolated pancreatic pain (%) | Fluid overload | Others SAE (serious adverse event) | Pancreatic stent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buxbaum et al. (USA, 2014) [30] | 0 vs. 17 | 0 vs. 25 | 23 vs. 39 | 8 vs. 22 | None | NA | 4 vs. 5 |

| Shaygan-Nejad et al. (Iran, 2015) [32] | 5.3 vs. 22.7(p = 0.002) | NA | 22.7 vs. 44(p = 0.006) | 5.3 vs. 37.3(p = 0.005) | None | NA | 9.3 vs. 10.7 |

| Choi et al. (Korea, 2017) [31] | 4.3 vs. 9.8(p = 0.016) | 0.4 vs. 2.0(p = 0.040) | 6.7 vs. 16.1(p = 0.001) | NA | 1 pts in study group | Not difference(3 pts for arm) | 15.3 vs. 13.7 |

| Park et al. (Korea, 2018) [34] | 3.0 vs. 6.7 vs. 11.6(ITT anal.*) | None | 18.9 vs. 23.9 vs. 20.9(ITT anal.*) | 12.1 vs. 17.9 vs. 20.2(ITT anal.*) | 1 vs. 3 vs. 0 pts | 8 vs. 7 vs. 2 pts | 22.0 vs. 19.4 vs. 14.7 |

| Masjedizadeh et al. (Iran, 2017) [36] | 12.9 vs. 25.8 vs. 32.3 | NA | NA | 21 vs. 33.9 vs. 43.5 | NA | NA | NA |

| Ghaderi et al. (Iran, 2019) [33] | 5.8 vs. 15.8(p = 0.013) | NA | 20.8 vs. 35(p = 0.014) | 7.5 vs. 27.5(p < 0.005) | NA | NA | NA |

| Guha et al. (India, 2023) [37] | 0.6 vs. 2.9(p = 0.118) | 0 vs. 60 | 0.6 vs. 2.3(p = 0.211) | 22.5 vs. 24.7(p = 0.7) | None | Bleed 2.2 vs. 1.7 %Perforation 2.8 vs. 2.9 % | 4.2 vs. 2.9 |

| Chang et al. (Thailand, 2022) [35] | 14 vs. 15(p = 0.84) | 3 vs. 4(p = 0.118) | 39 vs. 42(p = 0.67) | 19 vs. 16(p = 0.58) | None | 1 patient for group dead for sepsis | 2 vs. 5 |

*: Intention to treat analysis; NA: not available; PEP: post-ERCP acute pancreatitis; pts: patients

Studies comparing aggressive hydration with lactate Ringer: intra-procedural risk factors

| Author (country, year) [ref] | Difficult cannulation | Pancreatic duct cannulation | Pancreatic duct injection | Precut | Pancreatic sphincterotomy | Balloon dilation papilla | Trainee involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buxbaum et al. (USA, 2014) [30] | > 10 attemps13% LR10% SH | NA | 25.6% LR17.4% SH | 2.6% LR4.3% SH | 0% LR0% SH | 0% LR0% SH | Yes |

| Shaygan-Nejad et al. (Iran, 2015) [32] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 86.7% LR90.7% SH(p = 0.440) | NA |

| Choi et al. (Korea, 2017) [31] | 20.0% LR17.6% SH | NA | 2.4% LR3.9% SH | 8.2% LR5.5% SH | 3.5% LR3.1% SH | 8.6% LR9.4% SH | None |

| Park et al. (Korea, 2018) [34] | 34.1% aggressive LR36.6% aggressive NSS27.9% SH LR | NA | 15.9% aggressive LR12.7% aggressive NSS17.8% SH LR | 33.3% aggressive LR36.6% aggressive NSS31.8% SH LR | NA | 6.1% aggressive LR6.0% aggressive NSS3.1% SH LR | None |

| Masjedizadeh et al. (Iran, 2017) [36] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ghaderi et al. (Iran, 2019) [33] | NA | NA | 20% LR18.3% SH | NA | NA | 98.8% LR78% SH | NA |

| Guha et al. (India, 2023) [37] | NA | 15.2% LR17.8% indomethacin | NA | 26.4% LR32.8% indomethacin | NA | 8.4% LR3.4% indomethacin | Yes |

| Chang et al. (Thailand, 2022) [35] | 24% LR30% SH | 40% LR38% SH | 5% LR8% SH | 6% LR9% SH | 3% LR2% SH | 16% LR12% SH | Yes |

LR: lactated Ringer’s; NA: not available; NSS: normal saline solution; SH: standard hydration

The first prospective multicenter RCT on the efficacy of aggressive peri-procedural hydration with LR in reducing the incidence of PEP was published by Buxbaum et al. [30]. Although limited by the small number of patients, the study remains a milestone in the field and provides the basis for further studies. In a subsequent prospective, multicenter, double-blind Korean RCT [31], 510 patients at low and high risk of PEP were randomized 1:1 to two groups. The study showed a benefit in the vigorous hydration group. Two similarly designed prospective, randomized, double-blind trials by the same Iranian group, with 150 and 240 patients randomized 1:1, also had similar results [32, 33].

In another Korean double-blind RCT [34] comparing aggressive hydration with LR, aggressive hydration with normal saline, and standard hydration with LR, aggressive hydration with LR reduced the risk of PEP in moderate-to-high risk patients compared to standard hydration with LR. In addition, there were no statistically significant differences in PEP rates between the aggressive normal saline infusion group and the standard LR infusion group, suggesting that aggressive hydration is effective only when performed with LR solution. Furthermore, the need for a bolus immediately after ERCP was demonstrated in a trial where patients randomized to aggressive hydration did not receive any bolus [35].

Finally, two trials demonstrated the non-inferiority of aggressive hydration with LR compared to standard prophylaxis, (i.e., endorectal indomethacin) for the prevention of PEP [36, 37].

Meta-analyses have confirmed the protective role of aggressive hydration in the prophylaxis of post-ERCP acute pancreatitis and hyperamylasemia [38–42], even in low-risk patients [38]. Based on these findings, American guidelines suggest the prophylactic use of aggressive hydration with LR in unselected patients undergoing ERCP [15], while European guidelines recommend its use in patients in whom NSAIDs cannot be administered [13].

Despite such impressive results in well-designed prospective and RCTs, some criticisms can still be made. The first issue concerns the different protocols of aggressive fluid administration used in the above-mentioned trials. The so-called Buxbaum protocol, derived from previous experience in the treatment of acute pancreatitis, was used in the majority of trials [30, 32, 34]. Other trials reported differences in the bolus [31, 35] or lack of hydration during ERCP [33, 36, 37]. These differences are obviously manifested in the different volumes of LR received and the variable gap between aggressive and standard hydration volumes in the different trials. The effects on PEP prevention of aggressive hydration with LR may be affected by differences in the volume of fluid administered. In the study by Chang et al. [35], the difference between the mean total volume infused in the LR group and the standard hydration group was less than 1,200 mL on average (3,600 vs. 2,413 mL). Only two other trials reported the volume of fluid infused. In the study by Choi et al. [31], the volume of fluid administered was 2,744 ± 364 mL and 741 ± 63 mL (p < 0.001) in the vigorous and standard groups, respectively. In the study by Park et al [34], the volume of fluid administered during the 24-hour period was significantly greater in both the aggressive LR and the aggressive normal saline solution groups (4,183 ± 133 mL and 4,180 ± 117 mL, respectively) compared to the standard LR solution group (2,220 ± 69 mL; p < 0.001). According to the meta-analysis by Wang et al. [39], the hydration regimen with the highest efficacy of PEP prophylaxis is reported in the study by Buxbaum et al. [30].

One of the two studies comparing aggressive hydration with indomethacin is also open to criticism because the protocol of administering two doses of indomethacin, 50 mg before and 50 mg after ERCP, contradicts guidelines that recommend a single dose of 100 mg before ERCP [36]. This may explain the high PEP rate in the indomethacin group, which was closer to the placebo group than to the LR group.

In principle, the sample size and the heterogeneity of the method of sample size calculation could be considered as a critical issue. However, when evaluating the individual published trials, the size of the study population per se is not a major issue, nor is the pre-trial power calculation, because, for example, trials may be stopped for ethical reasons, resulting in smaller patient populations.

A comparison with standard hydration is no longer ethically justifiable, as it would be equivalent to comparing an effective prophylactic therapy to placebo, thus exposing some of the enrolled patients to unjustified health risks. There is also limited interest in comparing aggressive hydration with LR to indomethacin alone. Indomethacin has been shown to be effective [11, 12, 43, 44] with a negligible risk of adverse events. Further justification is provided by the trials shown below, which compared LR plus indomethacin to indomethacin alone to investigate a possible benefit of combination therapy.

Despite these critical points, the trials have considerable strengths. First, the primary outcome, i.e., acute pancreatitis, is identical in all trials. The rate and severity of PEP in patients receiving LR prophylaxis are statistically lower than in patients receiving standard hydration. In fact, two trials found a zero rate of severe acute pancreatitis [30, 37]. These results indirectly suggest that LR prophylaxis is beneficial in terms of costs and economic sustainability, by reducing the length of hospital stay and the additional costs associated with managing complications.

Concerning age, the samples and the different groups in each individual study are essentially comparable with regard to the risk of PEP, ranging from a minimum average of 43 years to a maximum of 59 years (Table 1). There were no major differences in sex distribution of the groups among the various trials. With regard to the patient-related risk classification for PEP, the majority of patients were at low and intermediate risk rather than at intermediate and high-risk (1,134 vs. 905). Regarding the presence or absence of intraprocedural technical risks, wherever they were reported, they appeared to be evenly distributed and therefore not able to affect the findings (Table 5). In this connection, even the difficult-to-interpret data from the Park et al. [34] study, which shows very high rates of difficult cannulation, pancreatic duct injection, or recourse to pre-cut, reinforces the idea that aggressive hydration is effective in highly complicated patients due to the combined presence of patient-related and procedure-related risk factors. Furthermore, while operator experience is a documented risk factor for PEP [45], it is noteworthy that the efficacy of aggressive fluid replacement with LR was invariably confirmed irrespective of whether trainees were involved [30, 37] or not [31, 34], and whether the study was single-center or multi-center. Finally, the exclusion of older patients with a higher risk of fluid overload probably resulted in the inclusion of individuals with a low risk of PEP [46], explaining the seemingly paradoxical finding that statistically significant results were obtained with a smaller patient population.

In conclusion, the current evidence presented in our review confirms the role of LR as a substitute for indomethacin in patients with contraindications to the use of NSAIDs, as reiterated in the guidelines.

The combined administration of endorectal indomethacin plus aggressive IV hydration with LR is reasonable because the two strategies, which have different mechanisms of action, may have synergistic effects. This combined prophylactic strategy has been investigated in 5 trials, summarized in Tables 4, 5, and 6 [47–51].

Studies comparing aggressive hydration with lactate Ringer plus indomethacin: study protocol design

| Author (country, year) [ref] | Study design | Intervention protocol | Comparison | Type of NSAIDs | Number pts | Female gender (%) | Patient related PEP risk | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mok et al. (USA, 2017) [47] | RCT (1:1:1:1), monocentre | LR + indomethacin (infusion protocol not available) | a. Standard NSS + placebob. NSS + rectal indomethacinc. LR + placebo | Indomethacin 100 mg | 48 per group | 48 vs. 60 vs. 69 vs. 73 | Average and high risk | Fluid overload increased risk*Active peptic ulcerElectrolyte alterationsPregnancyAge < 18 yrsAmpullectomy |

| Hajalikhani et al. (Iran, 2018) [48] | RCT (1:1), monocentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg immediately after the procedure + diclofenac | Standard hydration [LR 1.5 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, without bolus] + rectal diclofenac | Diclofenac 100 mg | 107 intervention group112 control group | 53.3 vs. 49.1 | Average and high risk | Gastrointestinal bleedingFluid overload increased risk*PregnancyAge < 18 and > 70 yrs |

| Thanage et al. (India, 2021) [49] | RCT (1:1:1), monocentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg immediately after the procedure + diclofenac | a. Aggressive hydration with LR (same infusion protocol)b. Rectal diclofenac | Diclofenac 100 mg | 57 per group | 52.6 vs. 43.8 vs. 63.1 | High risk | Acute pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Active peptic ulcerPregnancyAge < 18 yrs |

| Boal Carvalho et al. (Portugal, 2022) [50] | RCT (1:1), monocentre | 3.0 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, bolus of 20 mL/kg immediately after the procedure + indomethacin at the end of ERCP | Standard hydration [LR 1.5 mL/(kg h) during and for 8 h after ERCP, without bolus] + indomethacin at the end of ERCP | Indomethacin 100 mg | 83 intervention group72 control group | 53 vs. 48.6 | Average risk | Previous ERCPLow risk of PEPAcute pancreatitisFluid overload increased risk*Electrolyte alterationsAge < 18 yrsPost-surgical anatomy |

| Sperna Weiland et al. (Netherlands, 2021) [51] | RCT (1:1), multicentre | Bolus of 20 mL/kg within 60 min from the start of ERCP, followed by 3 mL/(kg h) for 8 h + rectal diclofenac | NSS with a maximum of 1.5 mL/(kg h) and 3 L per 24 h + rectal diclofenac | Diclofenac 100 mg | 388 intervention group425 control group | 60 vs. 59 | Average and high risk | Previous ERCPPancreatic head massAcute pancreatitisChronic pancreatitisSepsisFluid overload increased risk*Active GI bleedingElectrolyte alterationsAge < 18 and > 85 yrsPregnancyPost-surgical anatomy |

*: Cardiac, hepatic, respiratory or renal insufficiency/severe disease; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; LR: lactated Ringer’s; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; NSS: normal saline solution; PEP: post-ERCP acute pancreatitis; pts: patients; RCTs: randomized controlled trials; yrs: years

Studies comparing aggressive hydration with lactate Ringer plus indomethacin: results

| Author (country, year) [ref] | PEP (%) (experimental vs. control arm) | Severe PEP (%) | Hyperamylasemia (%) | Isolated pancreatic pain (%) | Fluid overload | Others SAE (serious adverse events between groups) | Pancreatic stent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mok et al. (USA, 2017) [47] | 6 vs. 21 vs. 13 vs. 19 | 0 vs. 0 vs. 2 vs. 0 | NA | NA | Only 1 patient in NSS + placebo group | None | 21 vs. 31 vs. 25 vs. 31 |

| Hajalikhani et al. (Iran, 2018) [48] | 0.9 vs. 2.7 (p = 0.622) | No severe PEP in the groups | 0.9 vs. 3.6 (p = 0.369) | NA | NA | NA | 2.8 vs. 2.7 |

| Thanage et al. (India, 2021) [49] | 10.5 vs. 15.7 vs. 14.0 | 1 patient in diclofenac group | NA | NA | 2 pts in LR + diclofenac arm1 in LR arm | NA | 10.5 vs. 7 vs. 3.5 |

| Boal Carvalho et al. (Portugal, 2022) [50] | 3.6 vs. 13.9 (p = 0.021) | 0 vs. 6.9 (p = 0.020) | 4.5 vs. 10.3 | NA | None | None | 16.9 vs. 16.7 |

| Sperna Weiland et al. (Netherlands, 2021) [51] | 8 vs. 9 (p = 0.53) | 5 vs. 8 (p = 0.23)°, 1 vs. 2 (p = 0.089)§ | NA | NA | 8 pts in experimental arm, 9 in control arm | None | 6 vs. 6 |

§ Atlanta Criteria; °: Cotton Criteria; LR: lactated Ringer’s; NA: not available; NSS: normal saline solution; PEP: post-ERCP acute pancreatitis; pts: patients

Studies comparing aggressive hydration with lactate Ringer plus indomethacin: intra-procedural risk factors

| Author (country, year) [ref] | Difficult cannulation | Pancreatic duct cannulation | Pancreatic duct injection | Precut | Pancreatic sphincterotomy | Balloon dilation papilla | Trainee involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mok et al. (USA, 2017) [47] | > 8 attempts13% LR + indomethacin13% NSS + placebo17% NSS + indomethacin10% LR + placebo(p = 0.87) | NA | 21% LR + indomethacin31% NSS + placebo25% NSS + indomethacin31% LR + placebo(p = 0.59) | 0% LR + indomethacin2% NSS + placebo0% NSS + indomethacin2% LR + placebo(p = 1.00) | 4% LR + indomethacin10% NSS + placebo13% NSS + indomethacin8% LR + placebo(p = 0.59) | 21% LR + indomethacin21% NSS + placebo19% NSS + indomethacin23% LR + placebo(p = 0.74) | 100% |

| Hajalikhani et al. (Iran, 2018) [48] | NA | 8.4% vs. 8%(p = 0.99) | NA | 21.5% vs. 21.4%(p = 0.99) | 6.5% vs. 7.1%(p = 0.99) | 42.1% vs. 33.9%(p = 0.26) | NA |

| Thanage et al. (India, 2021) [49] | > 8 attempts43.8% LR + diclofenac64.9% LR56.1% diclofenac(p = 0.88) | 10.5% LR + diclofenac7% LR3.5% diclofenac(p = 0.34) | NA | 26.3% LR + diclofenac5.2% LR22.8% diclofenac(p = 0.007) | NA | NA | NA |

| Boal Carvalho et al. (Portugal, 2022) [50] | NA | 13.3% vs. 13.9%(p = ns) | 8.4% vs. 8.3%(p = ns) | 7.3% vs. 9.7%(p = ns) | NA | 21.7% vs. 19.4%(p = ns) | NA |

| Sperna Weiland et al. (Netherlands, 2021) [51] | > 5 attempts30% LR + diclofenac29% control(p = 0.96) | 41% LR + diclofenac37% control(p = 0.37) | 15% LR + diclofenac17% control(p = 0.71) | 18% LR + diclofenac13% control(p = 0.06) | < 1% LR + diclofenac< 1% control(p = 0.63) | 5% LR + diclofenac7% control(p = 0.41) | 9% LR + diclofenac8% control(p = 0.89) |

LR: lactated Ringer’s; NA: not available; NSS: normal saline solution

In the first single-center small-sized study, Mok et al. [47] compared the incidence of PEP in four different groups of subjects at high risk of PEP. Prophylaxis conducted with indomethacin and LR was found to significantly reduce the incidence of PEP only when compared to the normal saline solution plus placebo (Table 4). Conversely, combining indomethacin with LR was no better than either intervention alone (although a trend towards lower PEP and readmission rates was observed).

In a larger Iranian study [48] and in a subsequent Indian RCT [49], combined prophylaxis with aggressive hydration with LR plus diclofenac showed no additional benefit over single prophylaxis strategies such as NSAIDs or aggressive hydration with LR alone. However, a subsequent prospective Portuguese study found significant superiority of the combined prophylaxis [50].

A recent network meta-analysis comparing different PEP prophylaxis strategies postulated that the combination of indomethacin and LR offered higher protection than single treatments [52]. However, the lack of RCTs directly addressing this research question should be pinpointed.

The recent Dutch FLUYT study, which was conducted in 22 hospitals and included a large number of patients at moderate to high risk of PEP, reached different conclusions [51]. The almost identical incidence of PEP in the two prophylaxis arms led the authors to conclude that PEP prophylaxis with NSAIDs combined with aggressive hydration with LR is not justified. Although this study [51] seemingly provides ultimate evidence against the benefit of combined prophylaxis, some clarifications need to be made. The aggressive hydration protocol used in this study, in which no LR was infused during ERCP, differed slightly from the so-called Buxbaum protocol. Another issue related to intra-procedural risk factors may have affected the findings of the study. Approximately 40% of patients enrolled were exposed to unintentional cannulation of the main pancreatic duct. However, given that PSP was left to the discretion of the operator, it was eventually placed in only 6% of patients in both groups (Table 6). Regarding the type of NSAID used in combination therapy, it should be highlighted that the most favorable results were obtained when the combination therapy included endorectal indomethacin [47, 50] and endorectal diclofenac achieved inferior rates of efficacy. Indeed, a network meta-analysis including 55 RCTs with a total of 20 different interventions in 17,062 patients comparing the effectiveness of different strategies to prevent PEP [53] found that the combination of high-volume intravenous LR plus rectal diclofenac 100 mg and the combination of standard-volume intravenous normal saline plus rectal indomethacin 100 mg were both more effective than rectal indomethacin 100 mg alone [53]. However, these combinations were not significantly more effective than diclofenac 100 mg rectally alone. The meta-analysis concluded that it remains to be proven whether different NSAIDs at different doses have different additive benefits when combined with intravenous fluids [53].

While further studies are eagerly awaited, aggressive infusion of LR in patients at low risk of fluid overload should be considered definitely safe. Indeed, as in the trials using prophylactic LR alone, all 5 trials shown in Table 5 showed a negligible rate of serious adverse events.

To summarize, trials have shown that LR is effective in preventing PEP. Further adequately powered studies will clarify whether combination therapy can be a valid option for PEP prophylaxis.

The present updated systematic review has identified 13 trials that investigated the role of LR in PEP prophylaxis: Eight trials evaluated LR alone, and five trials assessed LR in combination with NSAIDs. Irrespective of the patient population (i.e., in both small-sized and large-sized trials, and in patients at low, intermediate and high risk of PEP), trials have demonstrated the protective efficacy of LR for prophylaxis of PEP [30–34]. In addition, two comparative trials have reported the non-inferiority of LR prophylaxis to indomethacin, the current standard of care for PEP prophylaxis [36, 37]. Therefore, despite the variability inherent in the different infusion protocols used in the various trials, the substantial homogeneity of outcomes, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and results obtained make aggressive hydration with LR the prophylaxis of choice in those patients with contraindication to NSAIDs. The evidence for using the combined therapy with LR and NSAIDs appears to be more complex to analyze. In fact, although the first small-sized trials reported very promising results regarding the efficacy of the combination in prophylaxis [47–49], two trials with larger numbers of patients reached different conclusions [50, 51]. New trials are therefore needed to understand whether combination therapy can further reduce PEP rates compared with NSAIDs alone.

In published studies, the incidence rates of PEP range from 1–10% in low-risk patients to 8–20% in high-risk patients [3, 54]. Most cases of PEP are mild, but 11% are severe, with local and/or systemic complications, prolonged hospital stay, and mortality occurring in up to 3% of cases [3, 55]. Over time, despite efforts to contrast it, the incidence of PEP has not decreased but rather appears to be increasing. Along with impaired quality of life, performance status, and work capacity, the mortality and costs associated with PEP have increased proportionately [56, 57].

Of the many drugs tested for prophylaxis of ERCP, only endorectal NSAIDs exhibit documented efficacy. The Scientific Societies of Digestive Endoscopy recommend the use of endorectal NSAIDs for PEP prophylaxis. However, this recommendation has not been widely adopted, and recent surveys have shown that the use of NSAIDs in endoscopic practice is much lower than expected. A small proportion of patients have contraindications to the use of NSAIDs. Furthermore, non-use in some situations may depend on considerations that are not strictly medical. For example, the unavailability of diclofenac and the high cost of indomethacin in the USA may have limited the use of NSAIDs for PEP prophylaxis. In fact, the cost of a single indomethacin suppository has increased 20-fold to $340 between 2012 and 2019 [58]. In this scenario, identifying alternative prophylactic approaches is attractive.

As outlined in this review, in recent years there has been increasing evidence to support aggressive hydration with LR as an alternative role for NSAIDs in PEP prophylaxis. Combined prophylaxis with endorectal NSAIDs and aggressive hydration with LR solution has also been suggested. Currently, based on the evidence summarized in this review, the preferred infusion protocol appears to be that used by Buxbaum’s group. However, this approach may have some limitations in patients at high risk of either fluid overload or fluid retention. Moreover, the Buxbaum protocol involves a long period of treatment and therefore inpatient care, which is not compatible with the workload of some healthcare organizations offering ERCP on an outpatient basis. Finally, the aggressive hydration protocol can be difficult to administer, which may hinder its widespread use in clinical practice. However, despite these difficulties, since the publication of the earliest pioneering studies, aggressive hydration with LR has proven to be such an effective prophylactic strategy for PEP that it was promptly included in the guidelines as a recommended alternative to indomethacin.

In conclusion, presently solid literature evidence supports the use of aggressive hydration with LR for the prevention of acute pancreatitis after ERCP in patients unable to receive NSAIDs. Furthermore, the initial data showing a more protective effect of the combination of LR and indomethacin, have not been confirmed by more recent trials. Therefore, further studies are needed to evaluate prophylaxis in combination with aggressive hydration with LR solution and rectal NSAIDs.

ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

LR: lactated Ringer’s

NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

PEP: post-ERCP acute pancreatitis

PSP: pancreatic stent placement

RCTs: randomized controlled trials

The supplementary materials for this article are available at: https://www.explorationpub.com/uploads/Article/file/1001247_sup_1.pdf.

VGM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AL: Conceptualization, Validation, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. SG and FF: Writing—review & editing. RS: Validation, Supervision. All authors read and approved the submitted version.

Vincenzo Giorgio Mirante is the Editorial Board Member of Exploration of Medicine. Amedeo Lonardo is the Associate Editor of Exploration of Medicine. They had no involvement in the decision-making or the review process of this manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The data analyzed in this study was obtained from PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Requests for access to these datasets should be directed to Vincenzo Giorgio Mirante (v.mirante@libero.it).

Not applicable.

© The Author(s) 2024.

Copyright: © The Author(s) 2024. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

View: 1006

Download: 31

Times Cited: 0